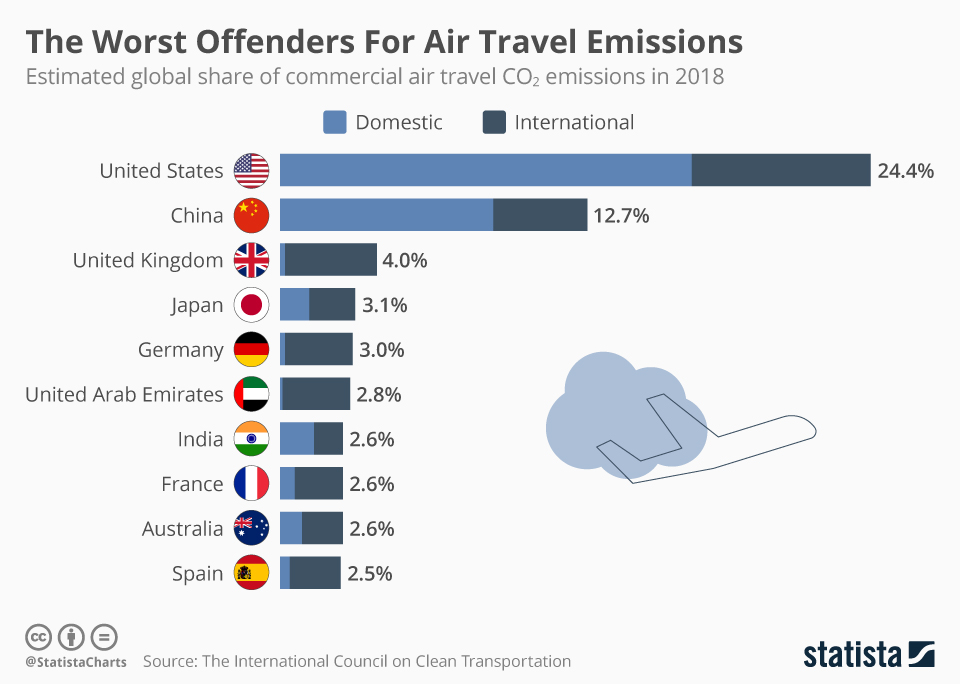

The statista post The Worst Offenders For Air Travel Emissions by Niall McCarthy (10/22/2019) produced the chart here. The post notes

The statista post The Worst Offenders For Air Travel Emissions by Niall McCarthy (10/22/2019) produced the chart here. The post notes

The 12 percent of Americans who make more than six round trips by air each year are actually responsible for two-thirds of all U.S. air travel and therefore two-thirds of all its emissions. Each of those travelers emits over 3 tons of CO2 per year and if everyone else in the world flew like them, global oil consumption would rise 150 percent while CO2 from fossil fuel use would go up 60 percent. As over half of the population does not generally fly, the U.S. ranks 11th in emissions per capita from flying.

The post references the icct report CO2 emission from commercial aviation, 2018. It notes

CO2 emissions from all commercial operations in 2018 totaled 918 million metric tons—2.4% of global CO2 emissions from fossil fuel use. Using aviation industry values, there has been a 32% increase in emissions over the past five years.

At the bottom of the icct report there is a link to spreadsheet data with air travel emissions data by country.