From NOAA’s Global Climate Report – February 2021:

From NOAA’s Global Climate Report – February 2021:

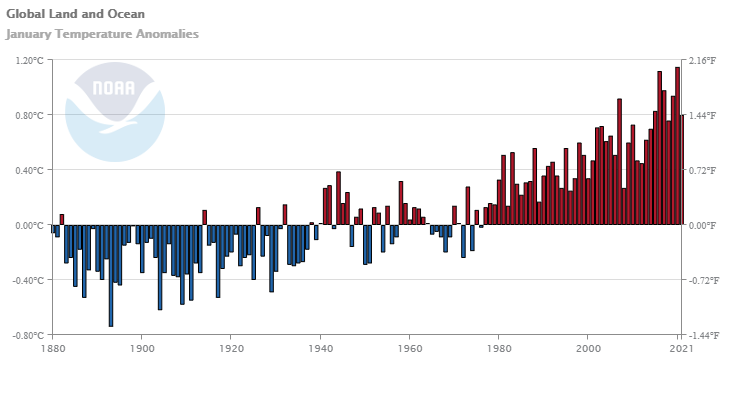

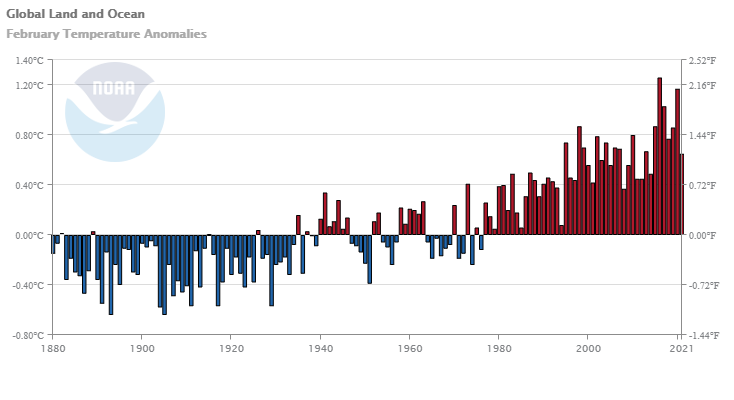

Averaged as a whole, the February 2021 global land and ocean surface temperature was 0.65°C (1.17°F) above the 20th century average—the smallest February temperature departure since 2014. However, compared to all Februaries in the 142-year record, this was the 16th warmest February on record.

Some context:

During the month, La Niña continued to be present across the tropical Pacific Ocean during February, helping dampen the global temperatures. Meanwhile, a strong negative Arctic Oscillation (AO) was also present during the first half of the month. Similar to the ENSO affecting global temperatures, the AO can influence weather patterns across the mid-latitudes. In a negative AO phase, the jet stream weakens and meanders, creating larger troughs and ridges. This allows really cold Arctic air to reach the mid-latitudes. Across the U.S., a trough over the central U.S. combined with a ridge over northern Canada to produce a Rex block, which is a blocking pattern that disrupts the jet stream and leads to more prolonged weather patterns. The AO on February 10–11 was -5.3, which essentially ties February 5, 1978 and February 13, 1969 for the lowest February value on record. They were also among the lowest 35 values for any day of the year (>99.9 percentile). By February 26, it had rebounded to +2.7 (97th percentile). The February mean AO was -1.2.

The time series data is available in the links in the additional resources box near the top of the article.