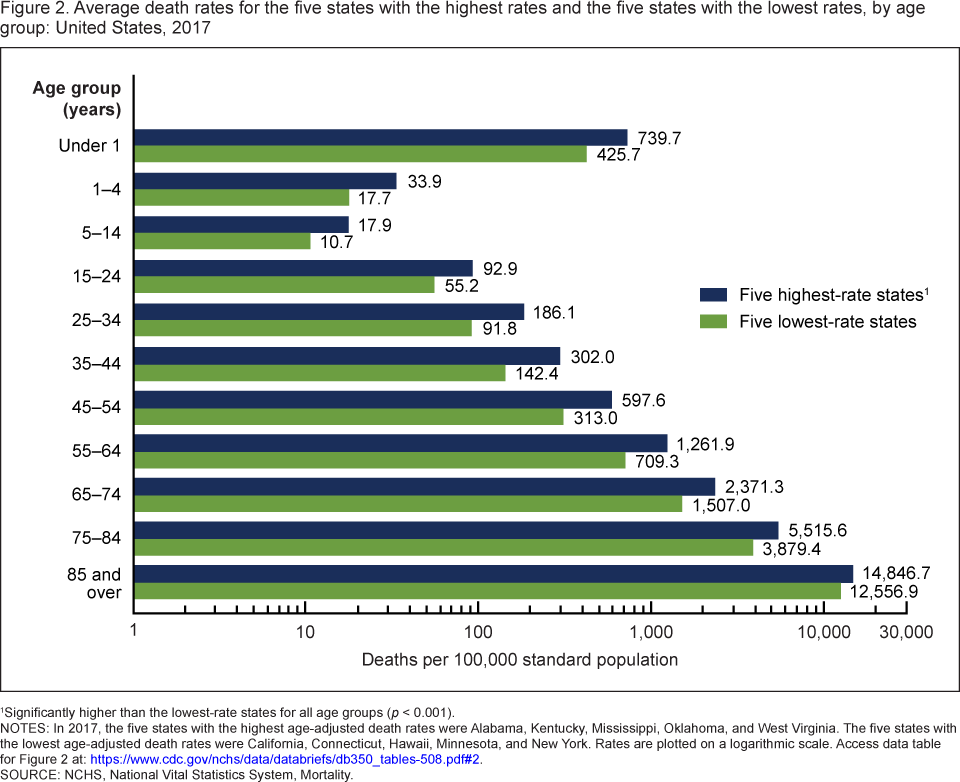

The CDC data brief, Mortality Patterns Between Five States with Highest Death Rates and Five States with Lowest Death Rates: United States, 2017 by Jiaquan Xu, M.D. (9/5/2019), provides the graph here of death rates by age (pay attention to the log scale on the x-axis). The five states with the lowest age-adjusted death rates: California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Minnesota, and New York. The highest: Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. By gender:

Among males, the average death rate for the states with the highest rates (1,094.3) was 48% higher than that for the states with the lowest rates (741.2).

Among females, the average death rate for the states with the highest rates (785.7) was 49% higher than that for the states with the lowest rates (526.4).

For Hispanics:

The rate for Hispanic persons was 27% lower (374.6 compared with 509.7) for the states with highest rates than for the states with the lowest rates.

There are four graph each with links to the data.