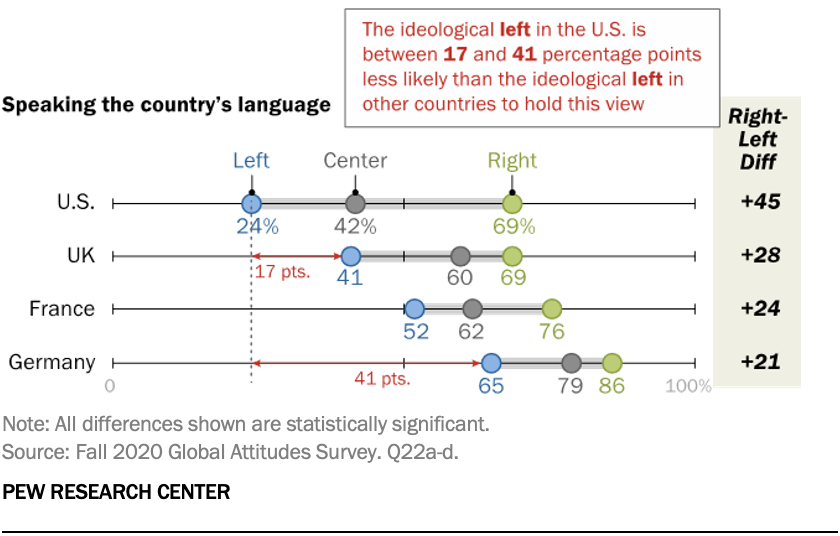

According to the pew article Growing share of Americans say their side in politics has been losing more often than winning by Ted Van Green (10/3/2022) overall 72% feel their side is losing more. There are, of course, differences by party:

According to the pew article Growing share of Americans say their side in politics has been losing more often than winning by Ted Van Green (10/3/2022) overall 72% feel their side is losing more. There are, of course, differences by party:

Today, about eight-in-ten Republicans and Republican-leaning independents (81%) say they feel that their side is losing more often than winning politically, up from 74% who said this in 2021. In February 2020, with President Donald Trump in the White House, just 29% of Republicans said their side was losing more often than winning, while 69% said it was mostly winning.

This makes some sense. When you control the presidency you are winning more. Yet,

Still, two-thirds of Democrats and Democratic leaners (66%) say their side is losing more than winning, up from 60% in 2021.

In early 2020, and at earlier points in Trump’s presidency, much larger majorities of Democrats said they felt like their side was losing more than winning. For example, 80% of Democrats said this in February 2020.

Controlling the white house doesn’t seem to be helping the Dems. How sustainable is a society if majorities always think they are losing?

As always, pew has a methodology section which can be used in a stats class.