The Census Bureau article Gains in Educational Attainment, Enrollment in All Hispanic Groups, Largest Among South American Population by Erik L. Hernandez and Kevin McElrath (5/10/2023) notes

The Census Bureau article Gains in Educational Attainment, Enrollment in All Hispanic Groups, Largest Among South American Population by Erik L. Hernandez and Kevin McElrath (5/10/2023) notes

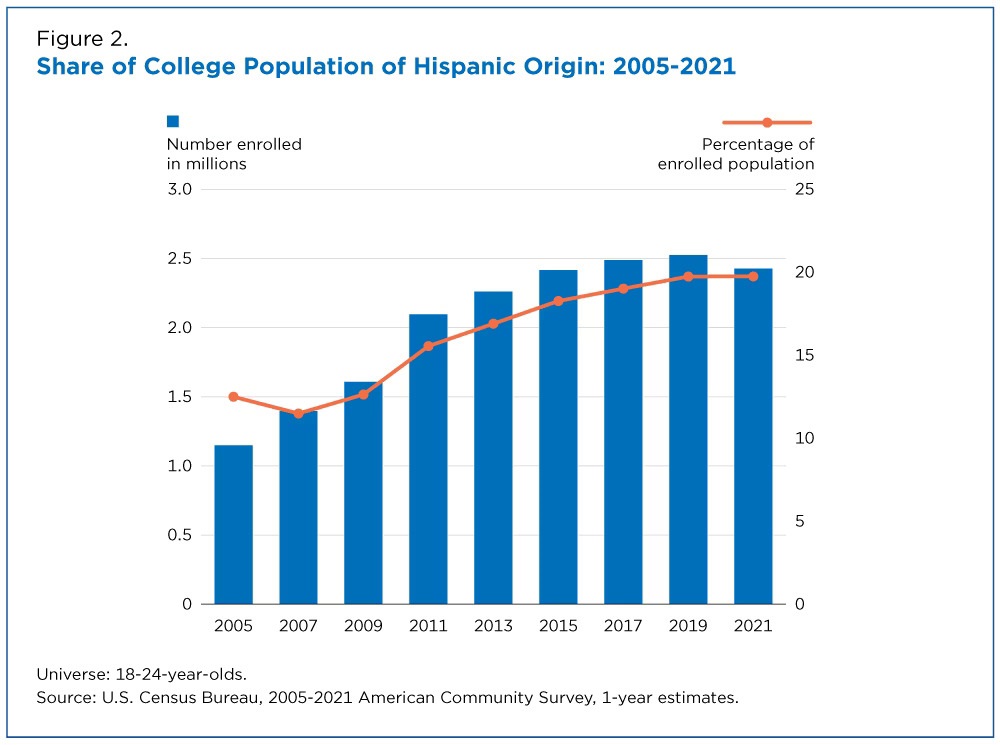

The number of Hispanic people ages 18 to 24 enrolled in college increased to 2.4 million in 2021, up from 1.2 million in 2005.

The share of all college students ages 18 to 24 who were Hispanic grew, too. The lowest share during the period (11.4%) was in 2006; by 2021 it had swelled to nearly 20%.

The article notes that in 2021 Hispanics made up 18.7% of the U.S. population, represented by the orange line in the graph. Does this mean that Hispanics are proportionally represented in college? Not necessarily so I’ll leave this as a research project. Hint: Proportions by age matter here.

There are three other graphs and reference to the data in the article.