The Climate.gov article, If carbon dioxide hits a new high every year, why ins’t every year hotter than the last by Rebecca Lindsey (9/9/19), provides a primer on the carbon dioxide and global temperature link, along with the role of the oceans.

The Climate.gov article, If carbon dioxide hits a new high every year, why ins’t every year hotter than the last by Rebecca Lindsey (9/9/19), provides a primer on the carbon dioxide and global temperature link, along with the role of the oceans.

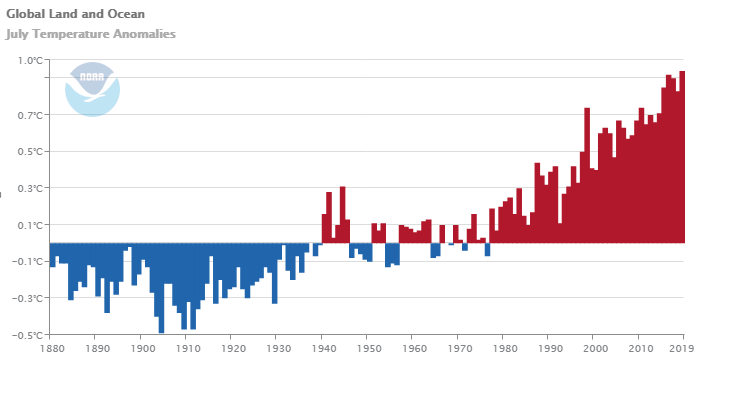

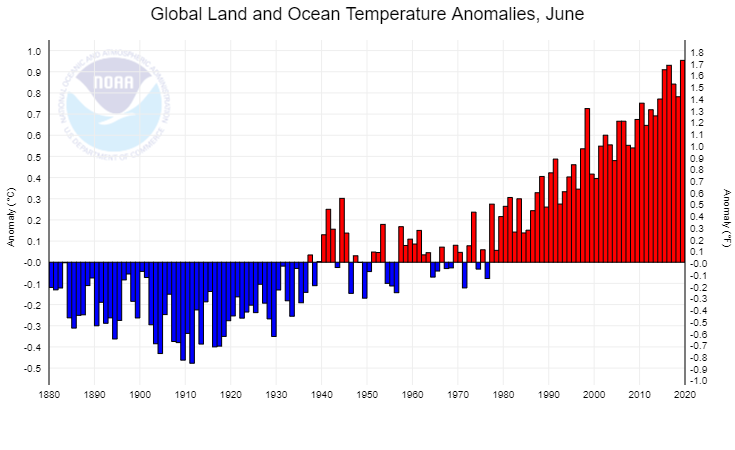

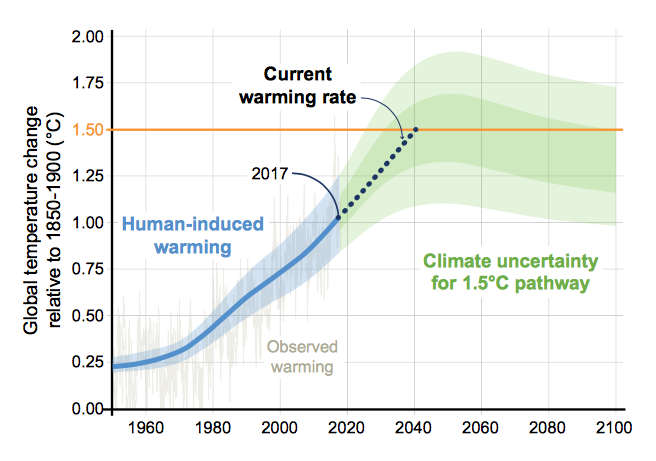

Thanks to the high heat capacity of water and the huge volume of the global oceans, Earth’s surface temperature resists rapid changes. Said another way, some of the excess heat that greenhouse gases force the Earth’s surface to absorb in any given year is hidden for a time by the ocean. This delayed reaction means rising greenhouse gas levels don’t immediately have their full impact on surface temperature. Still, when we step back and look at the big picture, it’s clear the two are tightly connected.

There are nice rate of change statements:

Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rose by around 20 parts per million over the 7 decades from 1880–1950, while the temperature increased by an average of 0.04° C per decade.

Over the next 7 decades, however, carbon dioxide climbed nearly 100 ppm (5 times as fast!). . . . At the same time, the rate of warming averaged 0.14° C per decade.

There is another graph, a fun cartoon, and links to the data.