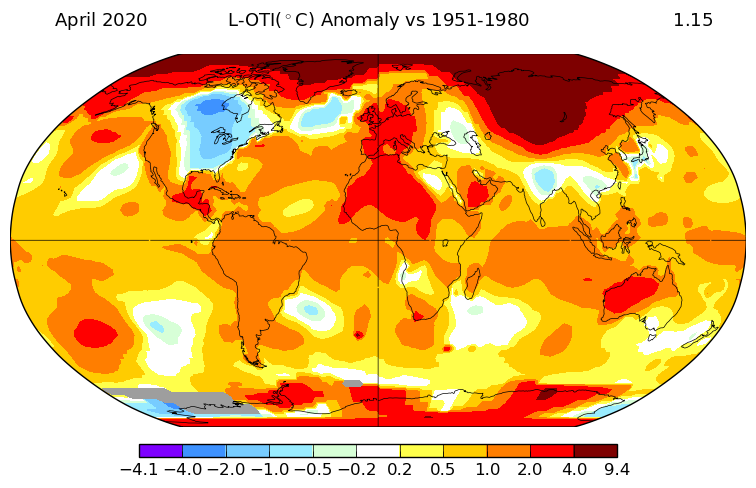

For those of us living in the northeast or a good part of the U.S. we might have felt that April was cold and it was. It is easy to use that as evidence that climate change is “fake news” yet it is good to keep in mind that if it is cold where you are it is likely much warmer somewhere else. The map here is from NASA’s GISS Surface Temperature Analysis page where similar maps can be made for a variety of time periods. Here we can see that for April 2020 parts of the U.S. and Canada where one of the few cold spots in the world. The rest of the planet was warmer.

For those of us living in the northeast or a good part of the U.S. we might have felt that April was cold and it was. It is easy to use that as evidence that climate change is “fake news” yet it is good to keep in mind that if it is cold where you are it is likely much warmer somewhere else. The map here is from NASA’s GISS Surface Temperature Analysis page where similar maps can be made for a variety of time periods. Here we can see that for April 2020 parts of the U.S. and Canada where one of the few cold spots in the world. The rest of the planet was warmer.

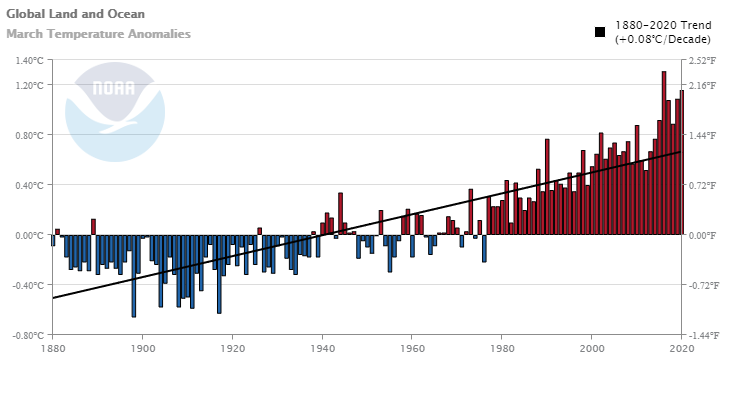

NOAA’s Global Climate Report – April 2020 notes:

Averaged as a whole, the global land and ocean surface temperature for April 2020 was 1.06°C (1.91°F) above the 20th century average of 13.7°C (56.7°F) and the second highest April temperature in the 141-year record. Only April 2016 was warmer at +1.13°C (+2.03°F). The eight warmest Aprils have occurred since 2010. April 2016 and 2020 were the only Aprils that had a global land and ocean surface temperature departure above 1.0°C (1.8°F).

Time series data is available on the NOAA page. Note that NASA uses 1951-1980 as their baseline while NOAA is using the 20th century. This accounts for the slight differences in their calculations on April’s anomaly from the baseline.

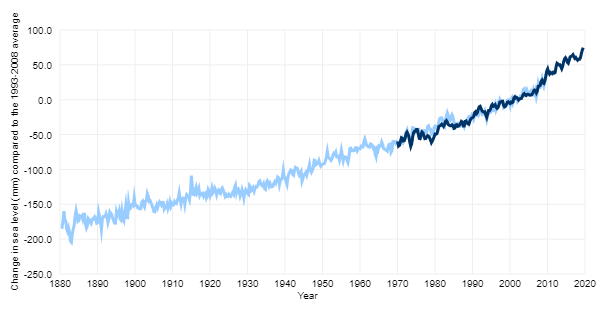

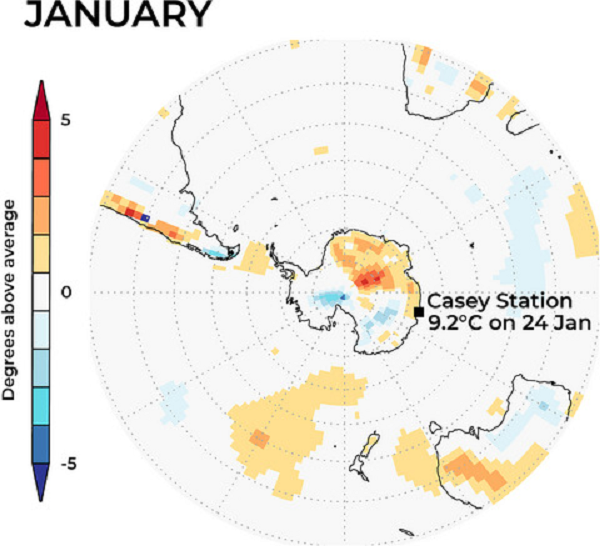

No, as can be easily seen by the graphic here copied from the NASA article

No, as can be easily seen by the graphic here copied from the NASA article