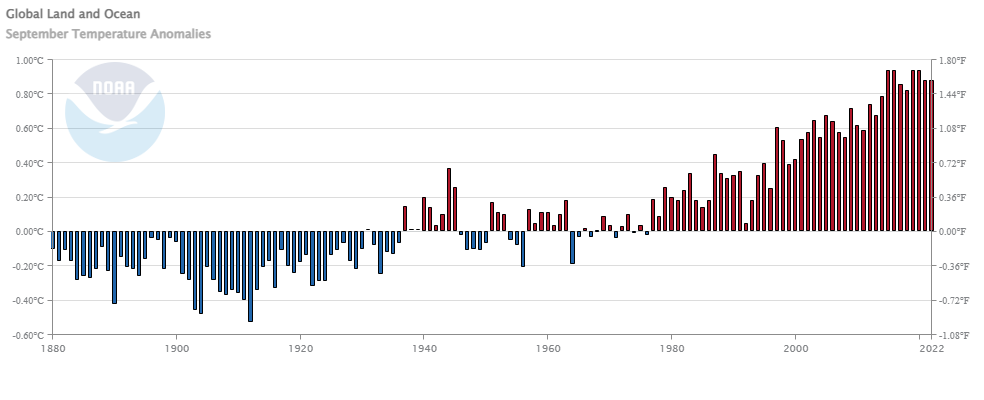

From NOAA’s October 2022 Global Climate Report:

From NOAA’s October 2022 Global Climate Report:

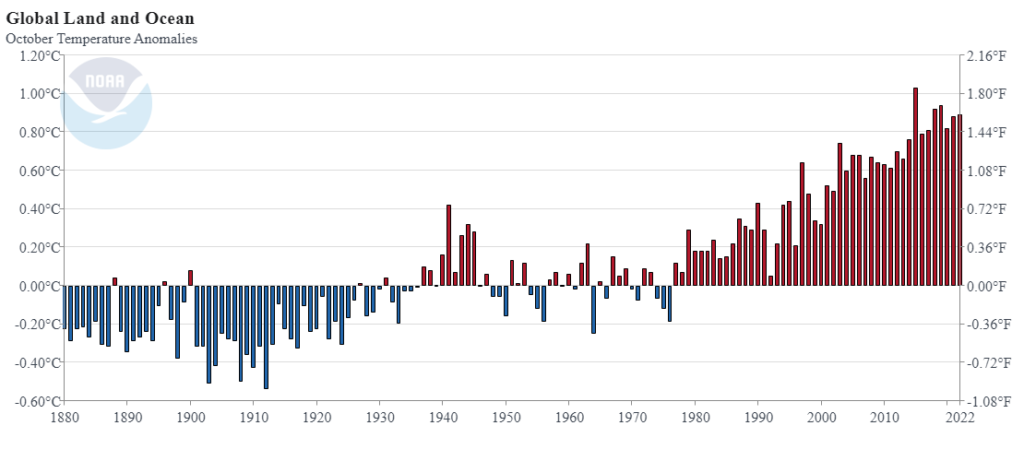

October 2022 was the fourth-warmest October in NOAA’s 143-year record. The October global surface temperature was 1.60°F (0.89°C) above the 20th-century average of 57.1°F (14.0°C). The past seven Octobers were among the ten warmest Octobers on record.

A few highlights:

Europe had its warmest October on record at 2.6°C (4.6°F) above the 1910-2000 average. This surpassed the previous record, set in 2020, by 0.38°C (0.68°F). More than seven countries in Europe recorded their warmest or joint-warmest October on record.

Austria had its warmest October on record. Austria’s national weather service reported that the average temperature was 2.8°C above the 1991-2020 baseline in the lowlands, and 4.0°C warmer in the mountains.

According to MeteoSwiss, Switzerland had its warmest October since the country began its records in 1865, with an average temperature 3.7°C above the 1991-2020 average.

Belgium tied 2001 for its warmest October on record, 3.1°C warmer than the 1991-2020 average, according to Belgium’s Royal Meteorological Institute.

MeteoFrance reported that France had its warmest October since records began in 1945, about 3.5°C above the 1991-2020 normal.

The time series data is available near the top of the page under Additional Resources.