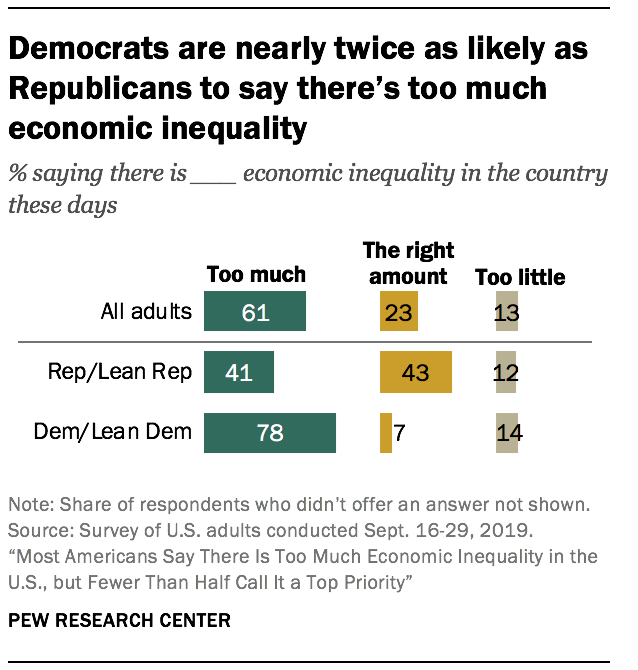

The PEW article Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call it a Top Priority by Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochhar (1/9/2020) is a thorough review of income and wealth inequality, as well as American’s views of inequality. For example, the graph copied here shows the responses to if there is too much economic inequality by political affiliation. A few highlights from the article:

The PEW article Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call it a Top Priority by Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochhar (1/9/2020) is a thorough review of income and wealth inequality, as well as American’s views of inequality. For example, the graph copied here shows the responses to if there is too much economic inequality by political affiliation. A few highlights from the article:

From 1970 to 2018, the share of aggregate income going to middle-class households fell from 62% to 43%. Over the same period, the share held by upper-income households increased from 29% to 48%. The share flowing to lower-income households inched down from 10% in 1970 to 9% in 2018.

As of 2016, the latest year for which data are available, the typical American family had a net worth of $101,800, still less than what it held in 1998.

While a majority of Republicans overall (60%) say that people’s different choices in life contribute a great deal to economic inequality, lower-income Republicans (46%) are significantly less likely than Republicans with middle (63%) or higher (74%) incomes to say this.

There are numerous graphs in the article and a methodology section which points to the data sources.