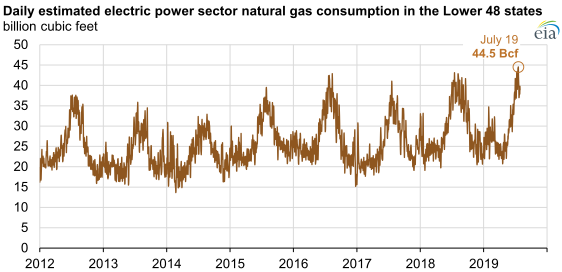

The eia reports that 44.5 Bcf of natural gas was consumed in the lower 38 on July 19 in their post United States sets new daily record high for natural gas use in the power sector by Katie Dyl (8/5/19).

Higher electricity demand for air conditioning during a heat wave from July 15 through July 22 drove the increased power generation, especially from natural gas-fired generators. Although the highest temperatures occurred during the weekend, most states east of the Rocky Mountains experienced warmer-than-normal weather in the days leading up to the heat wave. From July 16 through July 21, the average maximum temperature exceeded 85°F in most parts of the country.

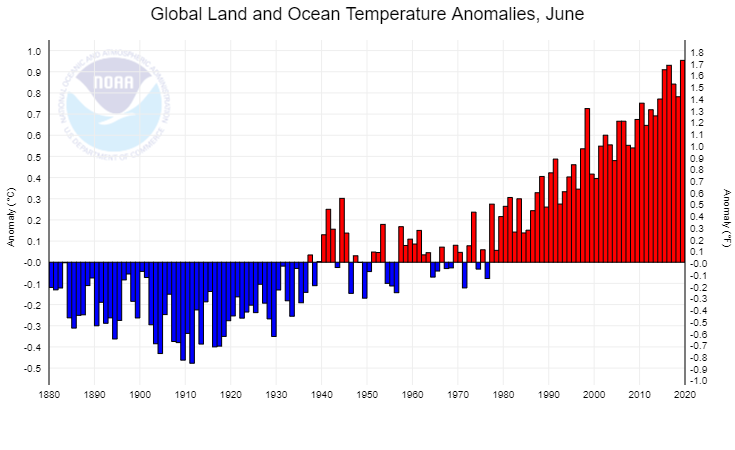

Note the feedback loop. As the planet warms we use more energy (still mostly fossil fuels) to cool homes and business (cooling takes more energy than heating) and thus emitting more co2 to warm the planet. The post has other graphs and links to the data.