Propublica’s article, Miseducation – Is There Racial Inequality at Your School? by Lena V. Groeger, Annie Waldman and David Eads, (10/16/18), provides data by state on the percent of nonwhite students, the percent of students who get free/reduced-price lunch, high school graduation rate, the number of times White students are likely to be in an AP class as compared to Black students, and the number of times Black students are likely to be suspended as compared to White students. The comparison is also available for Hispanic students.

Propublica’s article, Miseducation – Is There Racial Inequality at Your School? by Lena V. Groeger, Annie Waldman and David Eads, (10/16/18), provides data by state on the percent of nonwhite students, the percent of students who get free/reduced-price lunch, high school graduation rate, the number of times White students are likely to be in an AP class as compared to Black students, and the number of times Black students are likely to be suspended as compared to White students. The comparison is also available for Hispanic students.

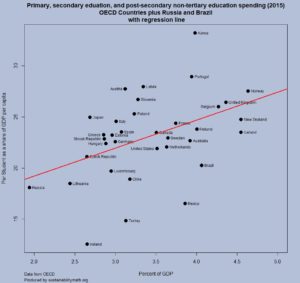

The graph here was created with their data and compares the percent of students on free and reduced lunch with the number of times Black students are likely to be suspended compared to White students (state data isn’t available for HI, ID, MT, NH, NM, OR, UT, or WY). The red lines uses all the data where as the blue line removes the outliers of DC and ND. The blue regression line has a p-value of 0.012 and R-squared of 0.15. This suggests that wealthier states, as measured by free and reduced lunch programs, have a greater disparity is suspensions between black and white students. The impact of outliers is instructive here and there are other scatter plots worth graphing from the article. There are also statistics projects waiting to be created with this data.

The article also has an interactive map or racial disparities by districts, but the map can be misleading based on missing data from districts. Can you see how? This makes the map itself useful for QL courses. R Script that created this graph. Companion csv file.