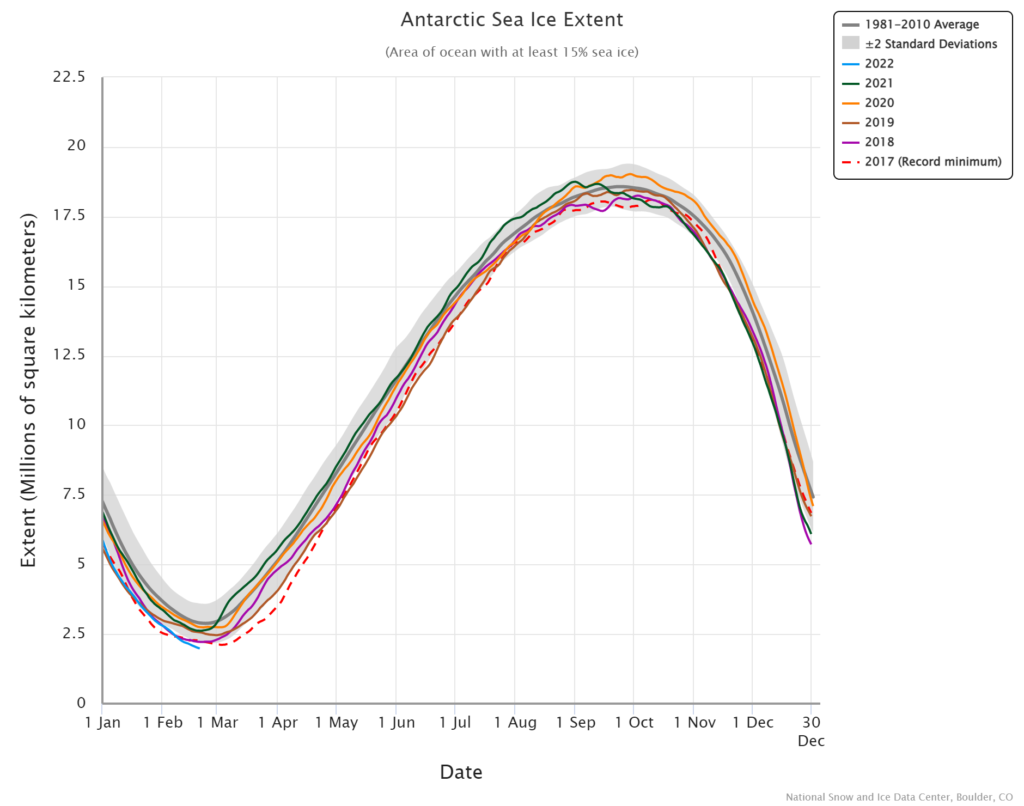

The paper New climate models reveal faster and larger increases in Arctic precipitation than previous projected by Michelle R McCrystall, et. el (11/30/2021) in Nature Communication has some great graphs. In fact, stop reading here and study the graph along with the caption; so much inf. Of course, the results are important too. From the abstract:

The latest projections from the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) point to more rapid Arctic warming and sea-ice loss by the year 2100 than in previous projections, and consequently, larger and faster changes in the hydrological cycle. Arctic precipitation (rainfall) increases more rapidly in CMIP6 than in CMIP5 due to greater global warming and poleward moisture transport, greater Arctic amplification and sea-ice loss and increased sensitivity of precipitation to Arctic warming. The transition from a snow- to rain-dominated Arctic in the summer and autumn is projected to occur decades earlier and at a lower level of global warming, potentially under 1.5 °C, with profound climatic, ecosystem and socio-economic impacts.

There are other excellent graphs in this paper. If you need great graphs to talk about look here. Plus, there are links to data sources at the end. If you want a quick overview see this NSIDC summary.