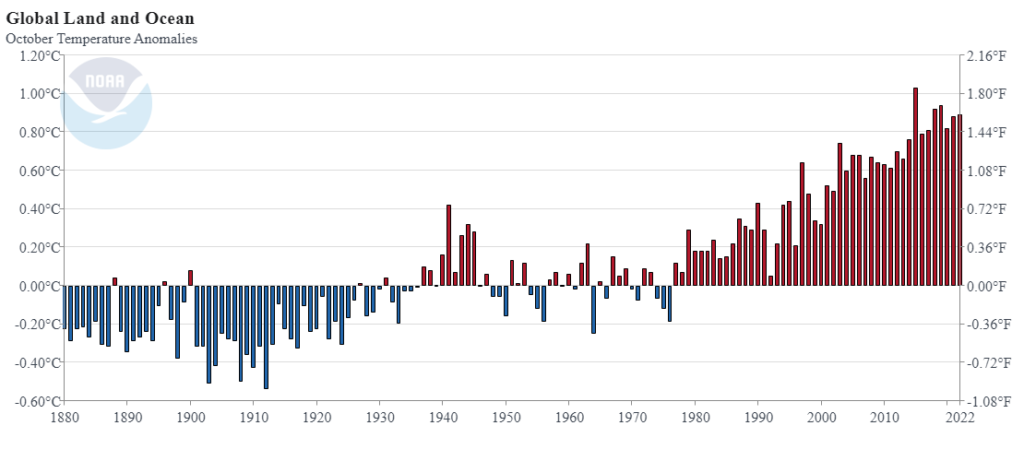

From NOAA’s November 2022 Global Climate Report:

From NOAA’s November 2022 Global Climate Report:

The November 2022 global surface temperature departure was the ninth highest for November in the 143-year record at 0.76°C (1.37°F) above the 20th century average of 12.9°C (55.2°F). Despite ranking among the ten warmest Novembers on record, this November was the coolest November since 2014. November 2022 marked the 46th consecutive November and the 455th consecutive month with temperatures, at least nominally, above the 20th century average.

A few of highlights:

Europe tied 2000 for its third-warmest November on record.

The contiguous U.S. had a November that was 0.7°F cooler than average.

However, New Zealand recorded its warmest November on record according to its state meteorological agency. The warmest three Novembers in New Zealand have all occurred since 2019.

Time series data is available near the top of the page.