The World Inequality Database summarize the paper by Bonneau and Grobon in the article Unequal Access to Higher Education (2/7/2022).

The World Inequality Database summarize the paper by Bonneau and Grobon in the article Unequal Access to Higher Education (2/7/2022).

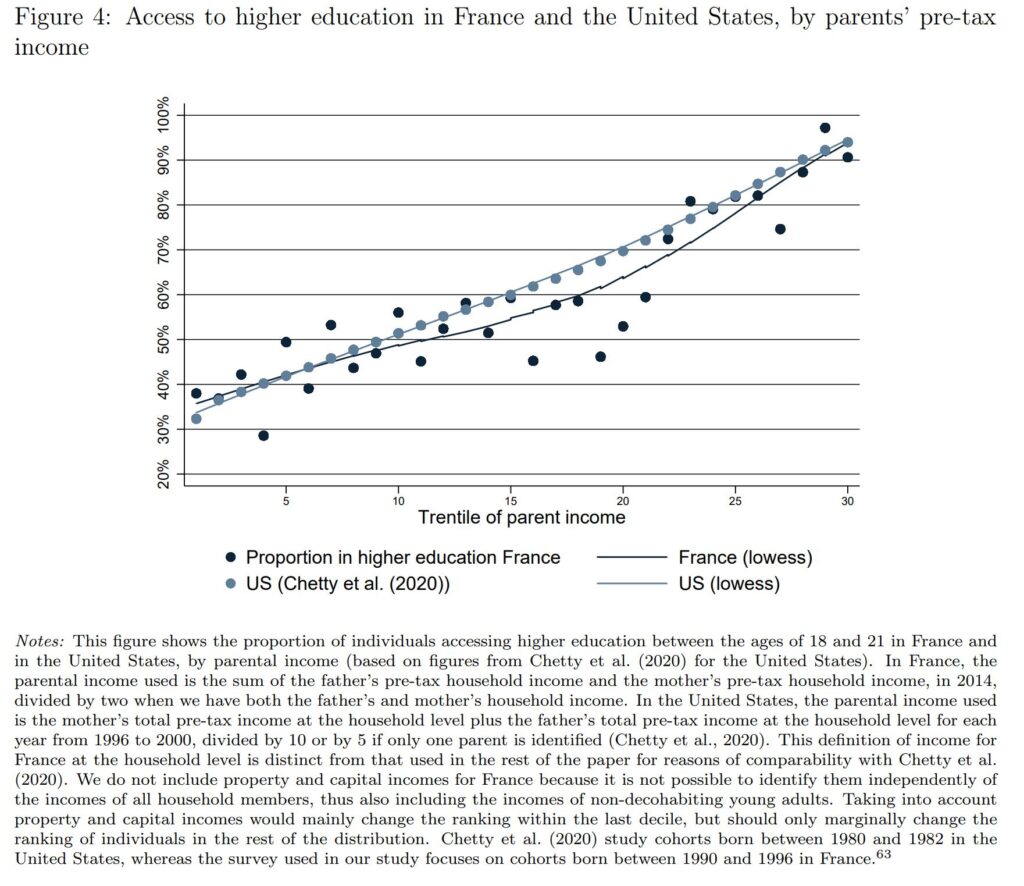

In this paper, Cécile Bonneau and Sébastien Grobon provide new stylized facts on inequalities in access to higher education by parental income in France. At the bottom of the income distribution, 35% of individuals have access to higher education compared to 90% at the top of the distribution. This overall level of inequality is surprisingly close to that observed in the United States. The authors then document how these inequalities in access to higher education by parental income combine with inequalities related to parental occupation or degree. Finally, they assess the redistributivity of public spending on higher education, and present a new accounting method to take into account the tax contribution of parents in our redistributivity analysis.

The article lists 11 key findings such as:

Inequalities in access to higher education create large inequalities in public spending on higher education: Those in the bottom 30 percent of the income distribution receive between 7,000 and 8,000 euros of investment in higher education between the ages of 18 and 24, compared to about 27,000 euros –of which 18,000 euros correspond to public spending and 9,000 to private spending through tuitions paid by parents– for those in the top 10 percent of the income distribution (Figure 5a);

The paper (link in the first quote) has numerous graphs and the details of the modeling.