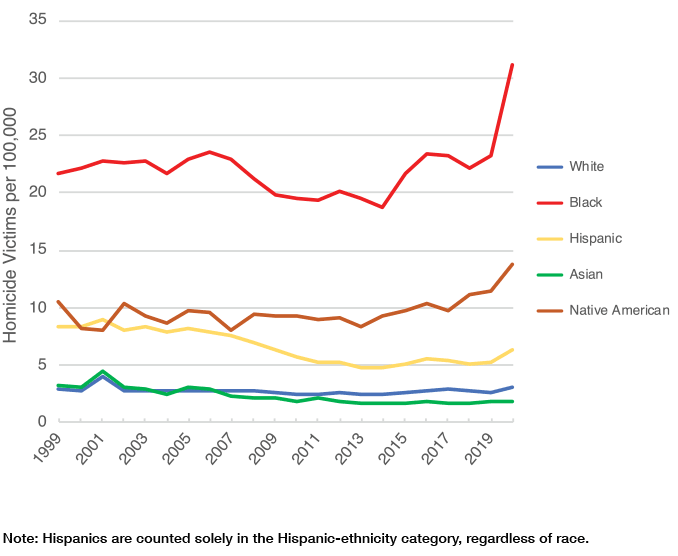

The chart here is from the National Center for Health Statistics paper Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020 by Donna L. Hoyert (2/23/2022). A definition:

The chart here is from the National Center for Health Statistics paper Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020 by Donna L. Hoyert (2/23/2022). A definition:

A maternal death is defined by the World Health Organization as, “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes” (1). Maternal mortality rates, which are the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, are shown in this report by age group and race and Hispanic origin.

Kevin Drum comments on this in his post The maternal mortality rate has skyrocketed over the past three years. A few quotes:

And the maternal mortality rate for everyone has nearly tripled since the late ’90s. Meanwhile, in Europe, the maternal mortality rate has been steadily dropping and is now about one-third the US rate.

What explains the differences by race according to Drum:

And we’re still in the dark about why Black women suffer such an astonishingly high rate of maternal mortality. As I said three years ago:

Poverty, education level, drinking, smoking, and genetic causes don’t seem to explain the black-white difference in maternal mortality. The timing of prenatal care doesn’t explain it. Medically, the cause of the difference appears to be related to the circulatory system, which is sensitive to stress. This makes the toxic stress hypothesis intuitively appealing, but it has little rigorous evidence supporting it. There’s some modest evidence that wider use of doulas could reduce both infant and maternal mortality, but no evidence that it would reduce the black-white gap.

Low income is weakly associated with higher maternal mortality rates, but it explains very little. The allostatic stress theory is appealing but probably wrong. And racism doesn’t seem to play much of a role either.

The CDC article has links to data.